Is self-care an essential tool for member care or a passing fad?

Tuesday 19 March 2024 10:35

Tuesday 19 March 2024 10:35 'Self-care ensures that one will thrive and flourish as opposed to merely survive and cope."

By Sarah Hay (who is HR and Member Care Manager for ECM Britain). This has been adapted from the latest issue of Lausanne Global Analysis.

Member care and self-care are not new concepts. However, marrying the two has been a more recent discussion, which gathered pace during the COVID pandemic.

The Global Member Care Network (GMCN) defines member care as follows: ‘Member care is the ongoing preparation, equipping and empowering of mission personnel for effective and sustainable life, ministry and work. Some mission organizations now use the term ‘staff care’, or even ‘staff care and wellbeing’ rather than member care. Whichever terminology mission organizations choose to use, the key elements are the care and resources provided to a missionary to enable them to thrive.

The World Health Organization defines self-care as ‘the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a health worker.’ We will look only at the self-care of an individual. It is that which a person does themselves, to enable them to be healthy enough in mind, body, and spirit to perform the functions that are required of them. Ohanian goes further: ‘Self-care ensures that one will thrive and flourish as opposed to merely survive and cope. Self-care is the unseen root system, deep, nourished, expanding, of a strong, resilient, blossoming tree.’ This imagery is very helpful in considering that self-care is not an easy fix but requires roots, time, and regular feeding.

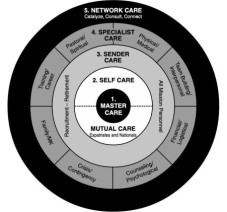

Perhaps the most well-known model that does mention self-care is that of Kelly O'Donnell and Dave Pollock as illustrated below.

Each of the five spheres are permeable, and care can flow between them. The sources of member care are included, eg senders, such as sending church or mission organization, as are the types of care, eg family and TCKs (Third Culture Kids). At the core of the model is Master Care, in recognition that God is the master, and it is from him that we receive strength. And it is him whom we serve.

The topic of sacrifice and how missionaries tackle the difficult issues of risk and suffering are well documented and indeed in my teaching on the MA in Member Care and MA in Staff Care and Wellbeing at Redcliffe College and All Nations Christian College, respectively, I have emphasized the need for new missionaries to develop their own theology of suffering and risk before they arrive on the field. The stories and images of Christian martyrs play an important role in Christian mission, but they can also cause a skewed theology of ‘it’s better to burn out than rust out’. Alongside the consideration of risk, we need to recognize that the call to consistently show up in what Eugene Peterson calls ‘a long obedience in the same direction can be a costly calling.

The widespread engagement with self-care during the pandemic has highlighted the power and potential of personal responsibility for wellbeing. Member care practitioners can harness this learning by revisiting the balance between personal responsibility and external intervention in missionary care. It requires a theological as well as a sociological and practical element to recognize that meaningful self-care is not a selfish practice, but an essential part of a missionary’s tool kit and one which the member care practitioner should encourage.

To read the full article please click here

To find out more about Sarah and her work with ECM Britain - click here

Archive > 2024 > March

- 31/03/2024 31/03/2024, 10:00 - Happy Easter!

- 29/03/2024 29/03/2024, 10:20 - On this solemn day...

- 25/03/2024 25/03/2024, 12:20 - Read our latest magazine now!

- 19/03/2024 19/03/2024, 10:35 - Is self-care an essential tool for member care or a passing fad?

- 12/03/2024 12/03/2024, 13:17 - Finding the Kingdom of God in our neighbourhoods

- 05/03/2024 05/03/2024, 14:48 - Come help us reach Muslims in Berlin!